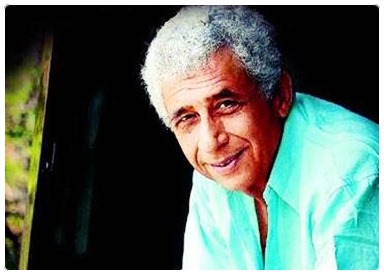

An Interview with Naseeruddin Shah – By R. Ansari

“Naseer!” The man yelled from two feet away from us. “Who would have thought I would run into you walking up Yonge St!” This was a South Asian man who stopped Naseeruddin Shah and myself as we walked up to catch a film at the Toronto Film Festival. “I have seen your films and they have been so important to me.”

Before we ran into this man I imagined writing for a Toronto newspaper and introducing Naseeruddin Shah as India’s Dustin Hoffman, or the thinking person’s Indian actor. I felt the insanity of meeting him in a city where nobody knew him, and living in another city (Lahore) where nobody can meet him (and, more importantly, see him perform on stage: he played Gandhil in Mahatama Versus Gandhi which has just completed runs in Mumbai and Delhi). Naseer signed the man’s package and allayed my panic.

Naseeruddin Shah’s roles in Shyam Benegal films made him an icon of the Indian New Wave Cinema of the 70’s. For me, a kid growing up in Karachi, he gave images that were memorable because they did not adhere to formula. But these films were not popular: your local videowallah still refers to them as “art films.” But the Ghalib Naseer played for Gulzar and Doordarshan crossed over into the popular imagination, and that includes the imagination of Pakistanis between Karachi and Mississauga, Ontario whose videowallahs keep only the Bollywood potboilers handy. Naseeruddin Shah was at the Toronto Film Festival showcasing two of the premiered films. I had a chance to talk to him about Such A Long Journey and Bombay Boys in the context of international productions which have Indian talent as engines, questions of audience, expatriate writing, political art, Pakistani cinema and the film he wants to make on Gandhi.

He expresses the same kind of anger and disillusionment, humor, frustration and compassion we expect from his onscreen performances. It seemed a strain on his voice to talk. And he neither smiled nor nodded. None of the usual gestures gave him away. I would sharpen a witticism, wait for an opening and only then would I get a smile out of this oyster. One more thing: His speech retains anglicisms from the 60’s. Like my father he can say: “Tell that Charlie to bugger off.”

RA: What did you think of Deepa Mehta’s Earth?

NS: Did not like it. Is there no other subject for these filmmakers? Is there nothing they can show from contemporary India? I know Partition is the most important subject, but the way Earth and Train to Pakistan treat it it does not move me at all. 3 pages of Manto tells you what you want to know.

RA: Earth is melodrama. It is the use of the Indian formula film genre to tell the story of Partition. What I like is that Earth kept within that formula.

NS: Earth is also the Hollywood formula. The sex scene was more important than the scenes of partition violence. Cinema cannot serve a didactic purpose. It cannot change the world. Cinema is not art either. I think an artist as a film maker comes along once a century. The best cinema can do is give images of the contemporary.

RA: What about the Indian cinema you were part of in the 70s?

NS: The so-called New Wave Cinema of the 70’s was not art. It was not a movement. It was a group of people. These filmmakers wanted anything but a formula film. So a lot of films were applauded that did not have merit. And they all lost money. So that now if you want to make a film off the beaten track you will have a hard time because of the memory producers have of those films. These days Mani Ratnam does well with finding the balance between the art and the commercial.

RA: You want to make a film yourself now, based on the play Mahatma vs. Gandhi. For a person who claims to not be interested in politics this is a hell of a subject. To put together a film you will have to pursue the project zealously.

NS (cracks a smile): I am interested in Gandhi the private person. Obviously his public life affected his private but I am interested in Gandhi the father. This is an area about which little is known. And it is not talked about. The play is about a father and a son, and I am interested in it because I had a difficult relationship with my father.

RA: What do you think of this international South Asian, but mostly Indian, cinema-making you are watching in Toronto? Indian novels are being made into films by Indians, or in collaboration with Indian talent. Will there be opportunities for roles, and storytelling of the kind you prefer?

NS: These writers and filmmakers are expatriate. They lack an intimacy. In the film Such A Long Journey, though the story is based around 1971, I feel there is such a distance from the Bangladesh War. I still felt 27 years away from it.

RA: Give me another example of this lack of intimacy.

NS: For example in Bombay Boys the Naveen Andrews character should have become a Bollywood star, and we should have seen what happens after that. But these expat filmmakers are not familiar with the industry, have not grown up with that… they would not know…

RA: So what would you have done if you were making that film?

NS: There are these 3 expatriates who come to Bombay in search of something. One of them finds out that he is a mediocre musician, another finds his brother. The third stars in a film, which is a hit, but leaves the film world at the end of the movie. I think he should have been shown to have found stardom. What happens to people who have talent, or no creative urge at all, when they become stars in Bombay? They actually believe people love them. Mr. Bachan to this day doesn’t understand why his films are failing. How can a superstar lose out on the love of the people? It does not even occur to him that he may be giving sub-standard product. Govinda the character is Govinda the person offscreen. But you have to be from the industry to know this.

RA: Perhaps these expatriate filmmakers, as you call them, are figuring out their audience.

NS: You don’t hear of writers and painters worrying about their audience.

There are very few writers writing in India. These people you hear of are all outside.

RA: What about cinema in Bengal or in the South?

NS: Telegu cinema is very big. They have big budgets and innovate on the formula. But it is impossible for me to act in the languages of the south. I tried. I had to repeat numerals for dialogue: ikees bees chabees STAEES!, ikees…. And then be dubbed over.

RA: What about playwrights?

NS: We do theatre in Bombay in Gujarati and Marathi and Hindi. But it is mostly Beckett, Ionesco, Pinter and Brecht. I wish we did plays written by Indians but there are, say, three Indian plays written in the last 50 years. It is difficult.

The censors are terrible. You can’t show corrupt officials. The kind of satire I saw in the Pakistani show Fifty/Fifty of the late 70’s would be impossible in India.

RA: Have you seen Pakistani films?

NS: Yes, some from the 70’s. Nadeem was a good actor. What are Pakistani films like these days?

RA: Formula films reign. Though the pace of Urdu film production has picked up over the last couple of years. Which means less rape and violence. The formula in Pakistan was the Maula Jat formula. It sired hundreds of Punjabi clones. They crowded out everything.

NS: Yes, the formula film. It’s the Sholay syndrome. What happened to Nadeem?

RA: He was part of it. Judging from cinema hoardings I remember from the mid-80s he tried his hand at playing the angry middle-aged man. He lives in Lahore.

Article originally published in Himal Magazine. Republished with compliment of R. Ansari, with thanks.