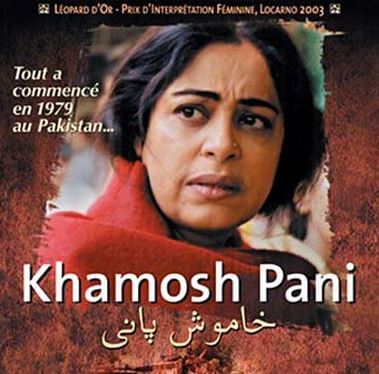

Talking to Sabiha Sumar about Khamosh Pani – By A. Arora

A documentary filmmaker, Sabiha Sumar surprised the cinema world with the all-compassing talent revealed in her first feature film, Khamosh Pani. The film has won innumerable international film awards, and Bollywood has also approached its lead player Aamir Malik

Anil Saari Arora talked to Sabiha Sumar at New Delhi, where the Pakistani filmmaker and her husband, producer S. Sathanandan, have presently set up base.

Anil Saari Arora: Is the film based on a story you had written?

Sabiha Sumar: When I write a story for a film, I am writing it from a film point of view, to develop it into a screenplay. It’s not really a literary piece but more a story that gives a structure for a script. But all the characters were there in my story – Ayesha and Salim, Amin and Shabbo, Mahboob.

A.S.A.: You create out Charkhi village a world that is unto itself.

Sabiha: Yes, I wanted the audience to get inside the world of Charkhi, because I thought it was a very important world; it had a very important story to tell. I wanted, of course, for the audience to get involved with the characters.

For me Charkhi was a forgotten world. Forgotten because the events of 1947 are hardly talked about in terms of the violence that was unleashed and the fact that nothing really returned to normalcy as such, and also forgotten because we tend to slip into situations and accept things very easily and we forget to question what is happening in our environment.

So Charkhi becomes then a symbol for a place where you develop bad habits about things – like you don’t question the Islamization process today, you don’t question the position of women, you don’t question various things and you say, Well, everything is fine, it’s not so disturbed. But when you really scratch the surface you find out that everything is very disturbed in fact, everything is very changed, everything is very different, that we are a completely different people today because of the processes that started in 1979.

So I wanted to go back and look at what those processes were, what was unleashed in that period that brought us to our present day situation. I very much wanted to link the past with the present.

A.S.A.: Did you have such a personal, family link to the partition yourself?

Sabiha: My parents came from Bombay to Karachi in August 1947. They came by ship. On the way they met a man called Abdul, who carried with him a small suitcase.He seemed to be talking to himself and was in a strange kind of a state. So my grandmother talked to him and he talked a lot about violence and how his family had been killed and so on. Then he opened his trunk, took out a little child’s dupatta, took out some glasses, took out some tumblers, various little remnants of his memory, and he talked about all of that. He obviously had nowhere to go when they landed in Karachi, so my grandmother adopted him.

As a child when I used to visit my naani, we saw Abdul there. Every time we went he would take the trunk out, show us all the things and talk about the same events. Then he would cry. It was a ritual. So in that way, Ayesha’s little trunk comes from that.

There are various things that I put together in that story which are from my own observations of life. So, of course, there are parts of me in that.

A.S.A.: Have you lived in a village yourself?

Sabiha: I’ve never lived in a village but I have worked very often in villages. So, I know the life quite closely. Because I come from a documentary tradition, I tend to research my films, so even Khamosh Pani is very close to reality in that sense, because the only way I could fictionalize it and imagine it was by keeping the images I had seen in life recur in the film.

I don’t really have an imagination that is independent of the reality that I research, that I see; and I allow that to grow and to take its own shape. Research is very important to me, and the village of Charkhi – actually the village of Wah where we shot the film – is a village that is just diagonally opposite Hassan Abdaal, where Panja Sahib is.

When I started doing my location search, I went to Hassan Abdaal and tried to find a village close to Hassan Abdaal to shoot in. I had traveled from Lahore to Rawalpindi by road and visited all the small villages, including Chakri, and Dehri, twin-villages in which a lot of violence happened during partition. I spent so much time in those villages that I was able to re-create that then.

A.S.A.: Khamosh Pani is a woman’s film actually, because Salim (the film’s male protagonist, played by Aamir Malik) emerges as the villain of the piece.

Sabiha: Even Salim, I always tried to portray him as a man with sensitivity. For example when he puts a picture of himself as a young boy in the trunk (which he discards in the stream) he knows he’s putting a piece of himself in his mother’s trunk, the piece that he had lost, that he cannot recover.

A.S.A.: Something he has chosen not to preserve?

Sabiha: He has chosen not to, or he cannot, because circumstances won’t allow him to. Maybe it is too dangerous to do it. Jab ek taraf hawa ka rukh hai, toh aap mein strength nahin hai ki aap doosri taraf jaa sakein. He knows that. Therefore he puts away ‘himself’ with the trunk. And the fact that he gives (his mother’s) locket to Zubeida (played by Shilpa Shukla), that is also a sensitive act because with that he is also saying that he recognizes the spirit in Zubeida to be the same as the spirit of his mother. That’s why he hands over the locket and removes himself from that situation.

A.S.A.: For me, at the end of the film Zubeida emerges as the real protagonist of Khamosh Pani, but a muted protagonist. Ayesha’s character (played by Kirron Kher) is very much a protagonist too, but both are muted protagonists.

Sabiha: The issue is that in Pakistan it’s as if women’s voice has been taken over, taken away by men and a patriarchal system which is extremely oppressive and powerful. I wanted to make my women strong, because they are strong, but I didn’t want to make them very vocal because they are not very vocal. I think they are waiting for a time when they can be vocal. I think Zubeida will be the woman who will speak when the time comes. She will be the first to speak and she will be the first to make amazing changes in society. It’s women like her who will do that, but for the moment these women choose to stay quiet.

A.S.A.: The dialogues in Khamosh Pani are fantastic, especially those between Ayesha and her friend Shabbo. Do these reflect your vision of life?

Sabiha: I think that is my vision of life in the sense that the discussion between the two women and the sensitivity between the two women is about questioning life, about questioning where they may have gone wrong. to deserve what is happening to them, and in the village these two also understand that these things happen to all of us, to the best of us. The loneliness we all have to come to terms with at a certain time in life; though when you are younger you think your children are ‘your everything’.

As the children grow older and find their different ways, you wonder if you were ever not alone? What Ayesha is talking about is the distancing of (her son) Salim in the intellectual sense, in the spiritual sense, and this is what is eating her up. (Because of the) forces that are acting on Salim, Ayesha is helpless. It’s a human situation. It’s human beings trying to make sense of their tragedy, trying to make sense of their loss, trying to make sense of life itself.

A.S.A.: But you never melodramatize this?

Sabiha: I think it’s like life itself, isn’t it? Reality is like that. We don’t make a scene about everything. For me the idea was to give a piece of life to the audience, exactly as I see it, exactly as I live it, and let the audience make up their own minds.

A.S.A.: How was the film received in Pakistan?

Sabiha: It’s been very well received in Pakistan.We did our Pakistan premiere in Wah village itself. The whole village came to see it and the whole village loved it.

It hasn’t been released yet in theatres, because we haven’t found a distributor yet. We are still working on this and we hope to release it in 2005. It has been released elsewhere, but in Pakistan there haven’t been films like this. There is no tradition for alternative cinema at all. So, a distributor can’t imagine what to do with it.

What we did was that we created our own traveling cinema and we did 41 screenings by traveling with it all over small towns and villages in Punjab, Baluchistan, everywhere.

A.S.A.: These were paid-for screenings?

Sabiha: No, we had free screenings because we didn’t want to get into getting tickets and everything done, and because we were funded by an organization that wanted it completely on a voluntary basis.

Now we have sort of given up on the idea of finding a distributor there. Our own company, Vidhi Films, has taken it on and we will be able to release it there.

A.S.A.: Salim’s character, a simple boy who’s got an artistic bent of mind – you know, it helped me to understand why so many young boys in India became Hindu fundamentalists.

Sabiha: I did want to show this transformation because it was very widespread in Pakistan – because we didn’t give the young people any options. In Wah, after the screening, a woman said, Salim was a lovely young man who played the flute, so why didn’t he think of becoming a big musician instead of becoming a big fundo?

If there had been a music school in the village, or in Rawalpindi or Islamabad, if the arts flourished in the country, the young men would have a chance to show off their talent – all young people want to be important in some way or the other, they want to contribute to society in some way, and they want to become heroes. But what are they going to do if they are not allowed to express their feelings?

For me the whole process of Islamization was really to take these reluctant young men and give them no option but to become important in this way.

A.S.A.: You’re from Sindh and you made a Punjabi film.

Sabiha: My story was written in English. Also wrote in English. It was Shoaib Haashmi sahib who translated the script. I would say that Shoaib sahib didn’t just translate it, he also interpreted it for the Punjabi language. You can’t do a literal translation of the dialogues, because then there’ll be no life to them. Jo uska mazaa thaa, uska jo juust tha, woh unhone bahut achhi tarah se liya. I had asked him to translate it to Urdu because we intended to shoot it in Urdu. You know, I had never imagined that I would learn Punjabi for this and be directing it in Punjabi.

However, when the Urdu script came and we began working on it, we realized that it wasn’t coming through, there wasn’t enough power in the words. Then I asked Shoaib sahib to turn it into Punjabi. The minute he did that everything fell into place, because it is a Punjabi story and you couldn’t tell it very well in another language. So I learnt Punjabi.

A.S.A.: What next?

Sabiha: I am working on a story of a young, lower middle-class, urban, modern young woman in Karachi city, who aspires to join the fashion and beauty industry, and it’s this journey of her’s through the class barrier and the language barrier – because the English-Urdu divide is very strong in Pakistan. It’s her story.